We’ve all heard the questions. “Why can’t we do things differently?” asks the front line employee. “Why won’t the boss enable the change we need?” asks the manager. “Does this organization want to change at all?” asks the boss, despairingly. While the initial answers to these questions are often personalized – it’s because of that executive person, or that group over there, or their culture – the true answer is often a failure to recognize and address the powerful economic force exerted by the currency of knowledge.

By their very nature, knowledge-based organizations attract an intelligent and inquisitive workforce. Employees, their managers and executives alike are aware of the power of the information that sits in their databases and flows across their computer screens. This information tells them how much business is being done, and whether key trends are going up or down. It tells them what parts of the organization are under most stress or which ones do the most work with the fewest resources.

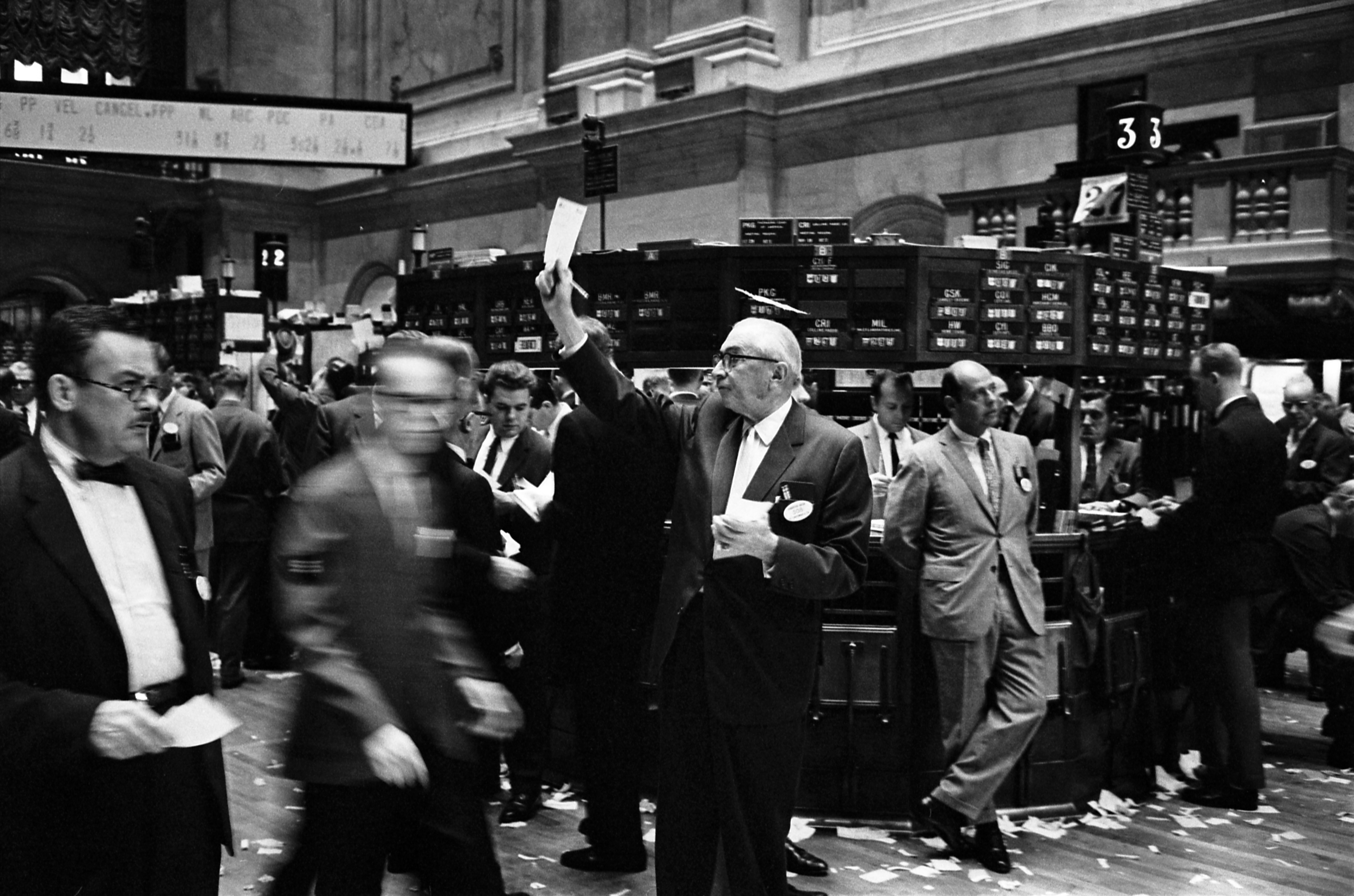

Within organizations where knowledge is the key currency in the “market,” maybe it’s not surprising that employees set themselves up in roles that are familiar in the broader economy. There are knowledge miners, who gather information and ensure its quality; knowledge brokers, who service the market for information they control, while making it known they control it; knowledge entrepreneurs, who see organizational or client opportunity with new or underused data. And in a topical nod to Russian influence, there are knowledge oligarchs, leaders of organizational units and owners of significant chunks of the overall information picture – an attribute that helps them set up symbiotic relationships with chief executives

Let’s keep with the Russian theme. In the Soviet Union, the system was stagnant. But some people did very well, particularly those at the very top of the chain (party bosses), and those in key industrial roles, who sat at the crossroads of political authority and the economic might needed to shore up the regime. In other words, the controllers of economic production and political influence (“oligarchs” and “brokers” in the terms I’ve used above) were comfortable, regardless of the impact on new ideas and entrepreneurship, or on the functioning of the economy at the front line. They weren’t averse to change necessarily. But change introduced risk into what was otherwise a safe place to be.

Now, whether you’re in private business or public sector work, it’s easy to recognize the innovative force of entrepreneurship. It was what was missing in the old Soviet bloc. In knowledge-based organizations, it’s the power of ideas. And if you’re an executive, you’re expected to empower that impulse and align it with the strategic goals of your company, branch or ministry.

Now, whether you’re in private business or public sector work, it’s easy to recognize the innovative force of entrepreneurship. It was what was missing in the old Soviet bloc. In knowledge-based organizations, it’s the power of ideas. And if you’re an executive, you’re expected to empower that impulse and align it with the strategic goals of your company, branch or ministry.

But if you’re going to shake up your organization, demanding new ideas and new projects which alter the way business is run and create new areas of knowledge, what you’re really doing is altering your knowledge economy, and that’s revolutionary talk! You’re giving power to new forces, and you’re making existing functions which get their influence from controlling information very nervous. You might think that everyone can see the merit in an innovative, dynamic organization – but if you fail to recognize and attend to the threat that knowledge entrepreneurship poses to these key folks’ sense of role and stewardship, you’re setting yourself up to fail. What’s more, from their influential perspective, what you’re doing may seem very wrong. You need them to get business done day to day. It will be hard to push back if they see threat and uncertainty.

The good news? There are ways to anticipate these issues and to tackle them in ways which, if not always painless, create greater dignity and opportunity in change. This is true even for those employees who have carefully brokered high value information and see that framework changing, and for senior players who have built a career at the helm of what is known. I’ll deal with how that can be achieved in next week’s blog.

[Next week: Change your knowledge market and avoid a crash]